My Atlanta, 1988 – 1998 A Reminiscence in Photographs

I arrived here in January 1987. It wasn’t my first time living in Atlanta. Actually, it was my third. The first was in the 1970s. My first wife and I lived in Chamblee then, in a tiny apartment on Buford Highway, working in factories, organizing the revolution. The Scottdale and Georgia Duck mills, an engine rebuilding plant, odd construction jobs. There were actually factories in Atlanta back then–GM, Ford, GE, Atlantic Steel, dozens more.

I grew up in Los Angeles, and Chamblee was perfect for me. With its strip malls, apartment complexes, and especially little of the thick vegetation that I swear made it hard for me to breathe (I had never even heard of a “de-humidifier” before Atlanta), it felt like home. Barren, working class, desolate. That was Chamblee in the 1970s. We were only here a few years then, but it’s where our son Michael was born. After moving around the Carolinas, in the early 1980s we found ourselves back, now with two boys. This time we lived in Hapeville, then East Point, then Grant Park. We were restless back then. That’s also when my life fell apart. I had done an excellent job of destroying our marriage, and in 1984 found myself living alone in Detroit, riding Greyhound buses down I-75 to see the boys, trying to salvage something out of the shards of the life I had shattered. Then I found photography.

What got me started was discovering that the only photos I had of my sons were taken by my father. Wanting to see them through my own eyes, I bought a camera, aimed it at the boys, and became obsessed. Took classes at Washtenaw Community College, roamed the streets and punk clubs of Detroit, and fell in with a wonderful group of actors in Ann Arbor who introduced me to the dark, moody 1960s New York theater photography of Max Waldman. I was reborn. The passion I had so deeply buried suddenly enveloped my life.

Then the world ended. Michael, nine years old, collapsed one day while living with me in the summer. He died four days later. A stroke. A blood clot caused by an aneurism in his heart. No symptoms, just sudden coma then death. I have never been able to describe this beyond the clinical details, and I can’t now. Four months later I was back in Atlanta.

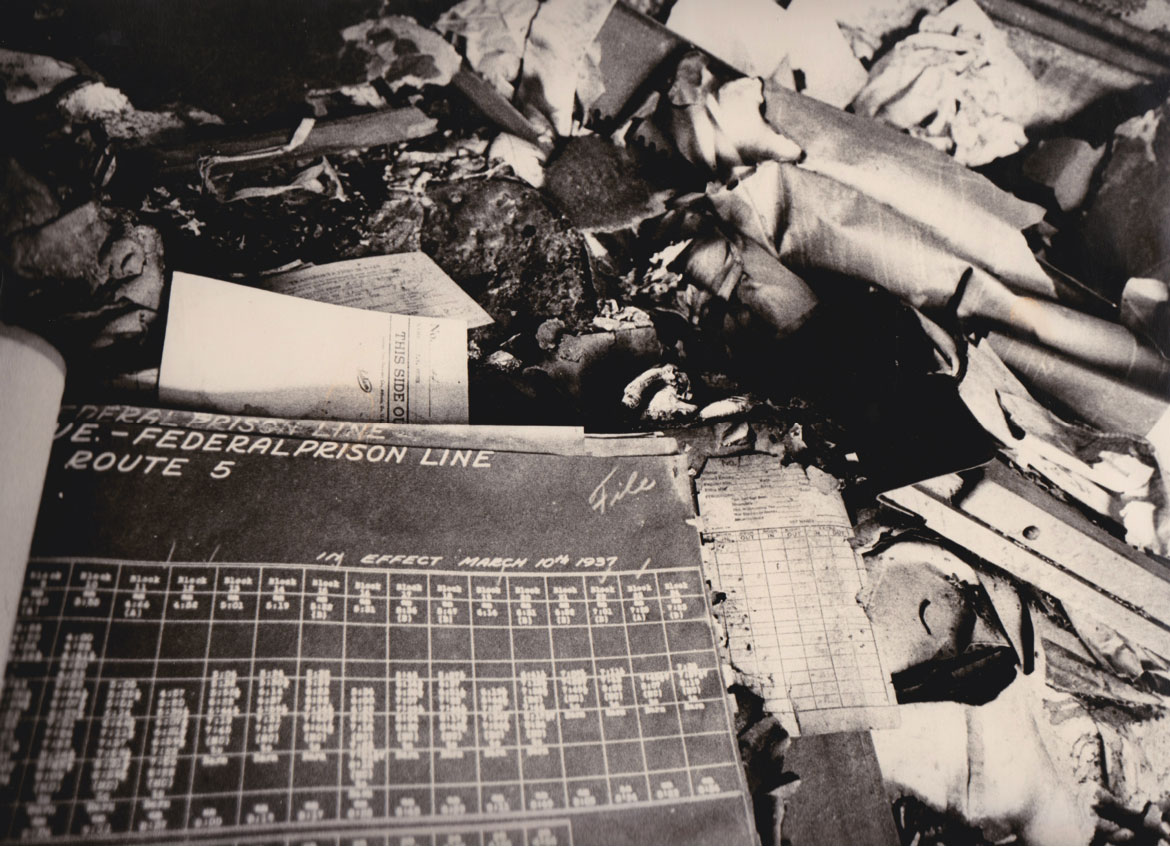

1988: The dead leave their stamp everywhere, stubbornly digging in. All those once thriving factories are now fractured, decaying shells strewn across the landscape like ancient fossils. Burned-out cotton mills, rusting railroad tracks, empty streets. Even luxury hotels from the “glory days” (whatever and whenever that was) are ghosts bolted to the concrete.

I can’t look at strangers’ faces through my camera, so I find myself amidst the lingering remnants of life once lived. Discarded, abandoned, forgotten, but still clinging. I discover that I glean a sliver of comfort in those crumbling ruins, and my camera loves them. Their quiet, decaying vigil wraps itself around my soul, and for a few moments my chest loosens slightly and I’m actually at peace. Working during the week as a typesetter at Williams Printing in Midtown, there are only two things that allow me to survive the weekends–Michael’s brother, Danny, and my forages through the ruins, trash heaps and discards of the city. Life and death. Nothing in between. I never exhibit these photos, just live with them.

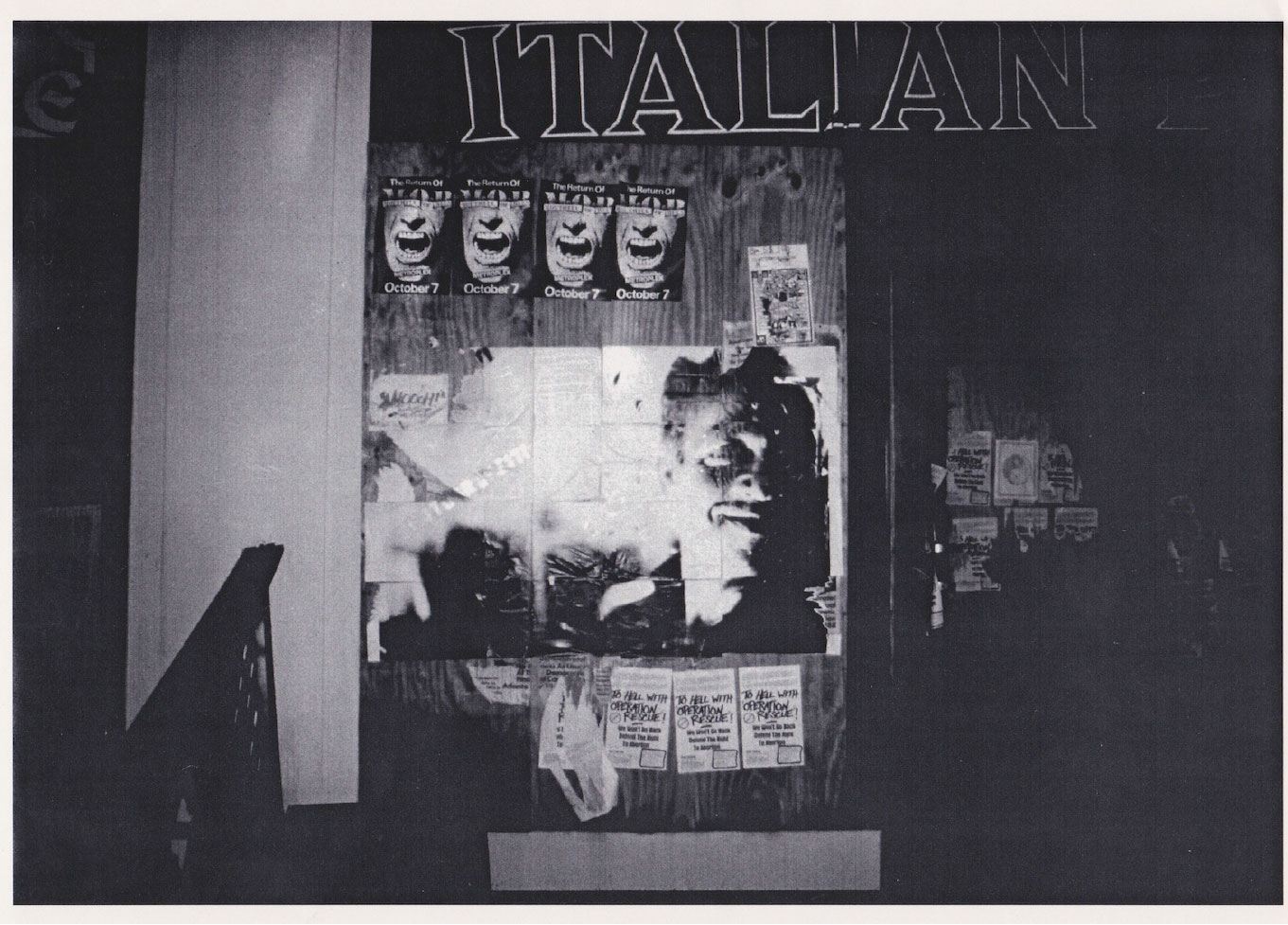

1989: But nothing stays the same, does it? What time doesn’t heal, it plugs up. Slowly, my camera finds faces, and I find the Atlanta Photography Group. There I meet a like-minded subversive, Ruth Leitman, and together we hatch a plan. Recruiting Lee Wilson, Luann McEachern, Tom Meyer, we become Fotografitti. Using Canon’s brand new color laser printer and working late at night, we create huge blow-ups of photographs and plaster them on those abandoned buildings throughout the city. Decay into beauty. We stay anonymous for a while, causing quite a stir, but go “legit” when we’re invited to do an installation at the Atlanta Arts Festival. Nothing lasts forever.

Emerging from my cocoon, I seek out the theater. That’s where I had begun to find passion in Detroit, and it’s where I turn here to find it again. I discover an emerging community. I begin shooting for the Center for Puppetry Arts, Seven Stages, Theatrical Outfit. I’m there at the first years of the Actor’s Express. Young, energetic, dynamic companies struggling to create a new world of theater in and for Atlanta. For the next ten years that world is my professional home. I’m the staff photographer for the Alliance Theater along with Actor’s Express and the CPA, and work with every theater in the city, from Georgia Shakespeare and Jomandi to the Atlanta Opera and Ballet. I’m privileged in these heady years to be a part of, and document from deep within, Atlanta’s theater renaissance.

And I meet Maryann. Art, work, and love merge as never before.

1990: So here’s how it begins. Across the street from Williams Printing stands the IBM tower, Midtown’s first high-rise. A beehive of white shirts and ties, but with a killer cafeteria. I go almost every day for lunch, and begin secretly photographing its denizens. Weird, blurry images of hunched backs and blank faces entombed in steel, glass and marble. Not great photographs, but the germ of a thought. They would ultimately become the centerpiece of an exhibit, In The Land of the Blind the One-Eyed Man is King, at the 1990 Atlanta Arts Festival and Georgia Museum of Art: a rickety wooden hut wall-papered inside and out with the photos, serenaded by Klimchak’s haunting deconstruction of classic torch songs.

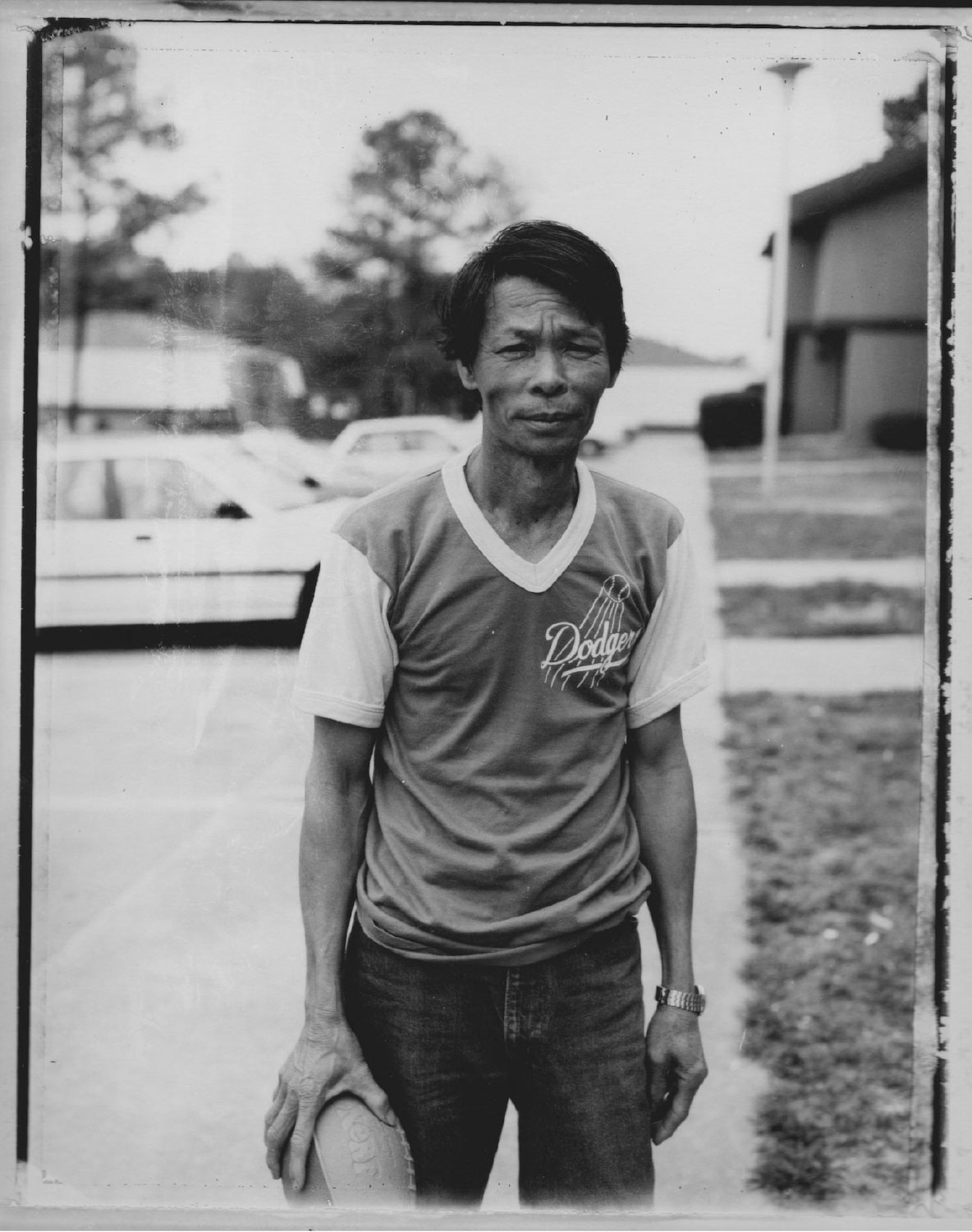

1991: Displaced in the New South. One day I overhear a man praising his life in the newly developed northern suburbs, where “You can find anything you could ever want.” Horrified at the thought of such a purposely bland world but intrigued, I head to the hinterlands of I-285 to explore and photograph: Perimeter Mall, Lawrenceville, Snellville. But here’s the rub. Amidst the beginnings of mass-market culture that would soon swamp the new Atlanta, pockets of a subversive world are growing like mushrooms. It’s taking root in hidden apartments, parks turned into soccer fields, run-down communities surrounding the chicken processing plants of Gainesville, and especially my old haunt: Chamblee. Immigrants from Mexico and Latin America, refugees from Vietnam and Eritrea. Here is where I find my home, my “New South.”

I’m an atheist and sometime revolutionary. I hail from Hollywood’s Laurel Canyon, a world apart from the South of deep roots and “sense of place.” Yet as I move through this new world my spiritual guide is the Southern Catholic writer Flannery O’Connor. In her short story, The Displaced Person, a Polish World War II refugee and his family are brought to work on a farm in a small Georgia town by the local priest. With this simple act the carefully constructed, deeply implanted social order of the rural South is, piece by piece, upended. Mrs. McIntyre, the mistress of the farm who had been struggling to survive since her husband died, is overjoyed at her good fortune and boasts to Mrs. Shortley, a white farm hand, “One fellow’s misery is the other fellow’s gain. That man there, he has to work! He wants to work! That man is my salvation!” Mrs. Shortley, in turn, is distrustful of the refugee, Mr. Guizac, believing he has brought all the evils of the world he fled with him (“The trouble with these people was, you couldn’t tell what they knew. Every time Mr. Guizac smiled, Europe stretched out in Mrs. Shortley’s imagination, mysterious and evil, the devil’s experiment station.”). She is aghast at the response of an old black farm hand to her complaints that Mr. Guizac and his family aren’t “where they’re supposed to be.” “It seem like they here, though,” the old man said in a reflective voice. “If they here, they somewhere.”

Everything changes when Mrs. McIntyre discovers that Mr. Guizac has paid a black farm hand to marry his cousin, who is still in Poland, so that she can come live on the farm. Livid, she confronts him, “I cannot understand how a man who calls himself a Christian could bring a poor innocent girl over here and marry her to something like that. I cannot understand it. I cannot!” To which he responds with a shrug, “She no care black, she in camp three year.” The Displaced Person, with no connection to the South’s “eternal” social order, is no longer a boon but a threat.

“He’s extra and he’s upset the balance around here,” she complains to the priest, who shocks her by responding “He came to redeem us.”

In the story’s haunting conclusion Mrs. McIntyre, Mrs. Shortley, and the black farm hand lock eyes with each other “in one look that froze them in collusion forever,” as a runaway tractor breaks Mr. Guizac’s back, killing him.

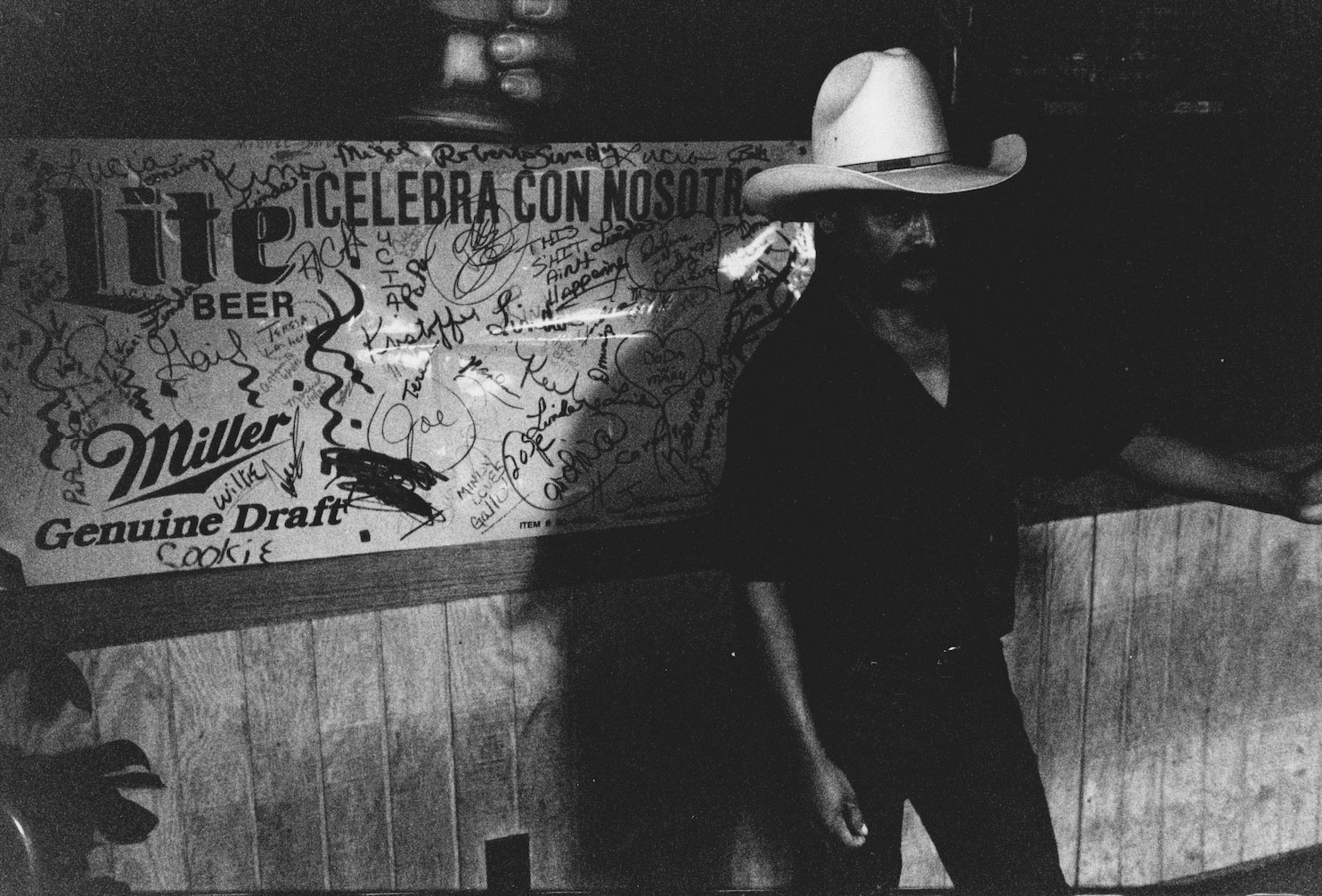

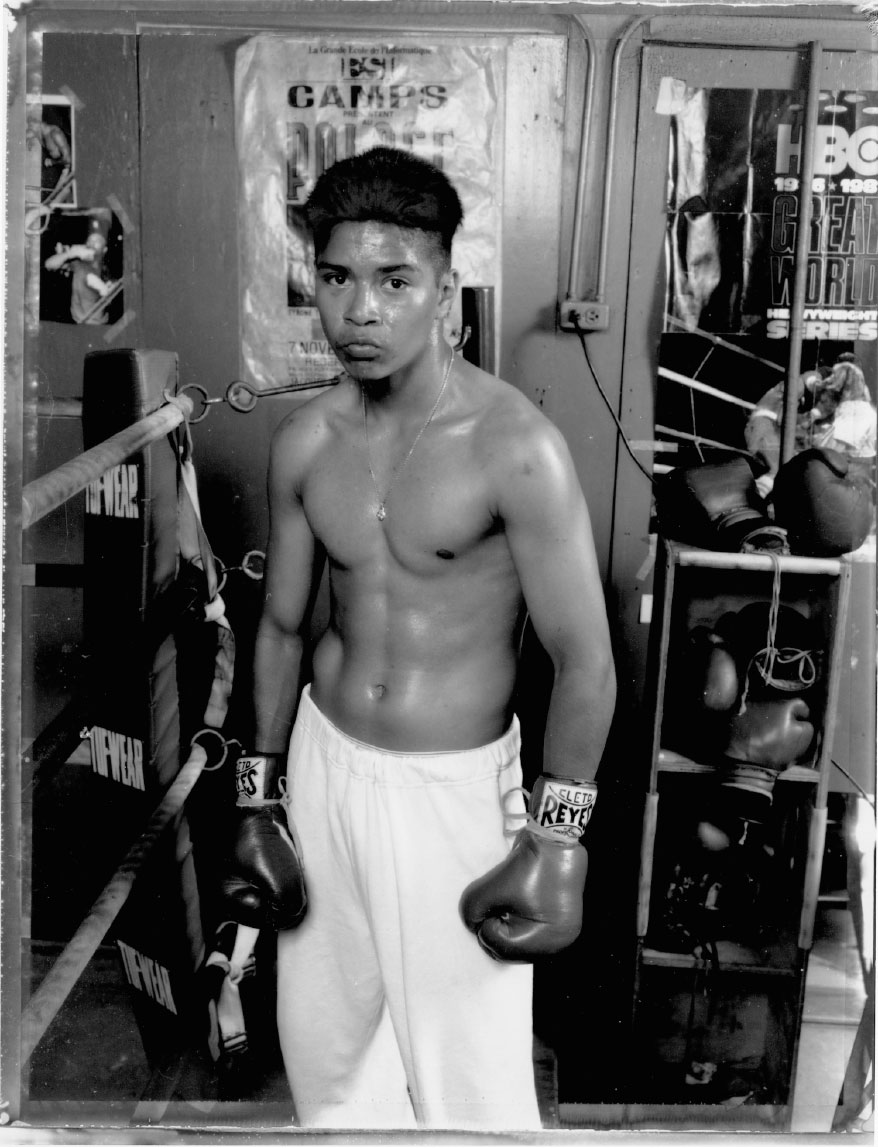

Flannery O’Connor’s Christ parable speaks directly to the dramatic changes I see emerging in and around Atlanta: Mustache Mike’s, a hole-in-the-wall honky tonk on Buford Highway, is now “Mustacho Miguel’s” where Mexican and Anglo locals mix, dance and shoot pool. An old warehouse on the edge of Doraville is now the International Ballroom, filled to the rafters with immigrants while featuring local and international Mexican and Vietnamese acts. The Doraville Boxing Gym is a second home for white, black, and Mexican youth with Olympic dreams. My old Chamblee apartment complex now houses Vietnamese musicians and refugee teens attending Cross Keys High School, where they are taught by teacher and stand-up comedian Suttiwan Cox. As Save The Children director Xuan Sutter tells me, “What really makes this the ‘New South’ is the fact that we are here.”

They came to redeem us. Along with photographer friends Lee Wilson and Aster Haile, I spend three years roaming through these haunts and many more: The Buford Highway Flea Market, various nightclubs, and the chicken farms and processing plants of Gainesville. I watch as the INS, counting on the collusion Flannery O’Connor so vividly portrayed, raids the processing plants, sweeping up “legal” and “illegal” alike.

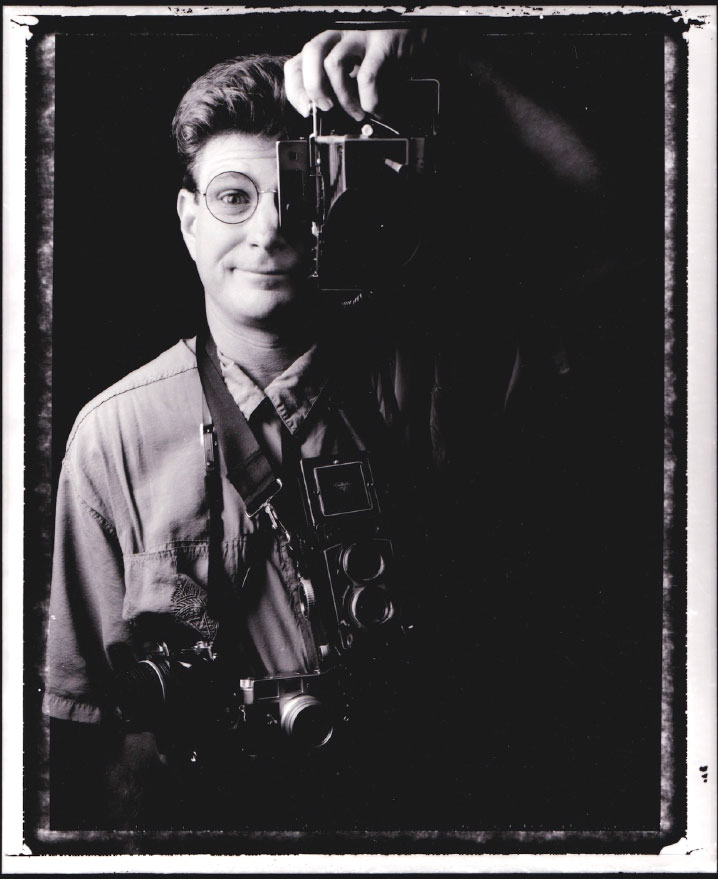

Our work becomes the exhibit Displaced In The New South, shown at Colony Square, the Fulton County Library, and Gainesville College in 1992 and 1993. Early on, I had discovered the joys of working with an old Polaroid camera and 665, the only positive/negative film they make. My portraits are printed almost life size. Hungry for more, I ask my friend Eric Mofford, an independent filmmaker, to help me turn the work into a film, and Displaced In The New South premieres at the Georgia Historical Society and on PBS in 1995.

1992: Lying in bed one night, I am frozen with the thought that I had just lived a full day without thinking or crying about Michael. I’m horrified. Life does indeed “move on,” but not for Michael. I find a snapshot of me and Michael that Danny had taken when he was just six and Michael was 8, and I start blowing it up on an oversize Xerox machine, over and over again until it’s so big the picture has almost blown apart. But we’re still there, dots on a piece of paper. The work is exhibited at the Nexus Art Center in 1994.

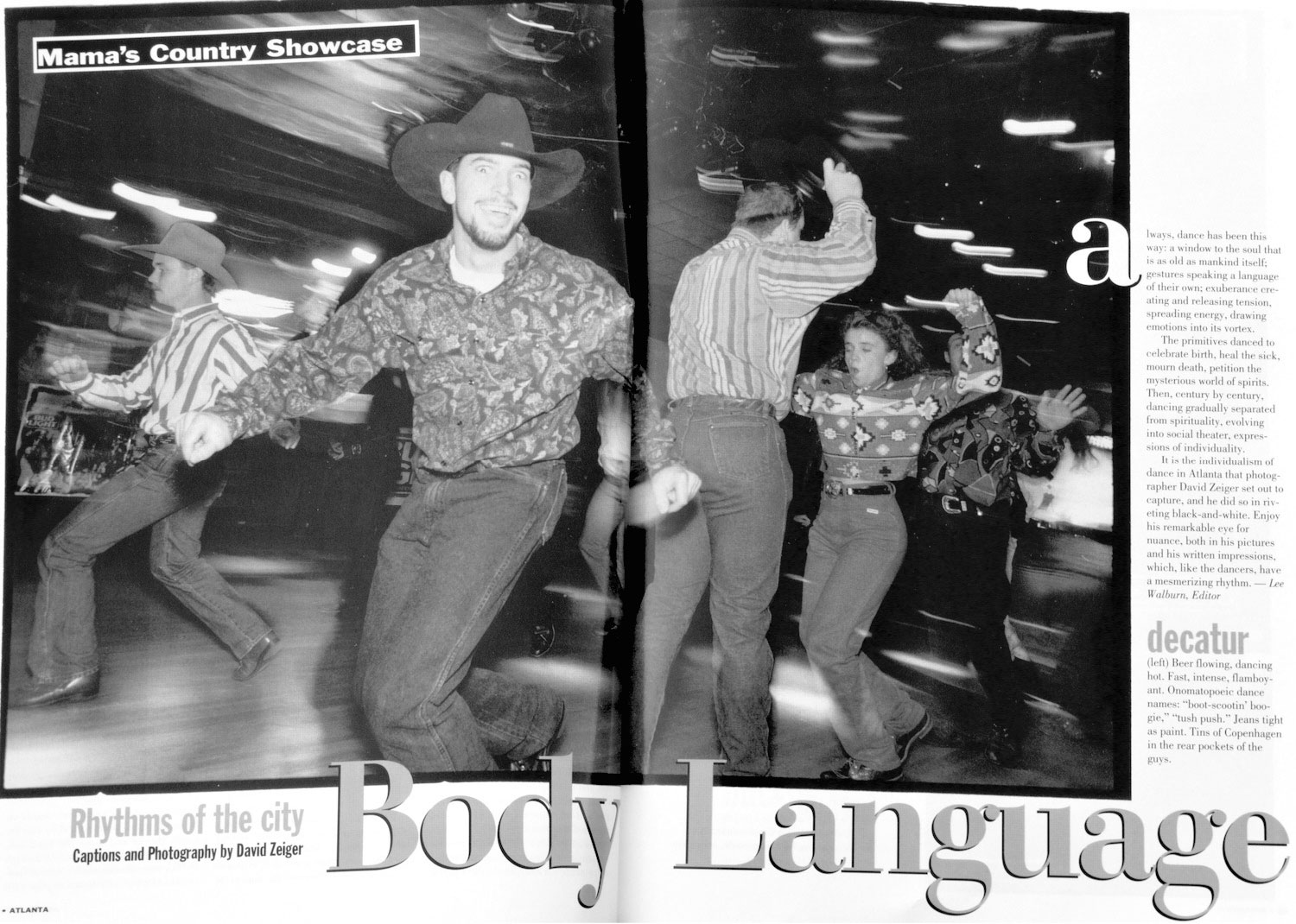

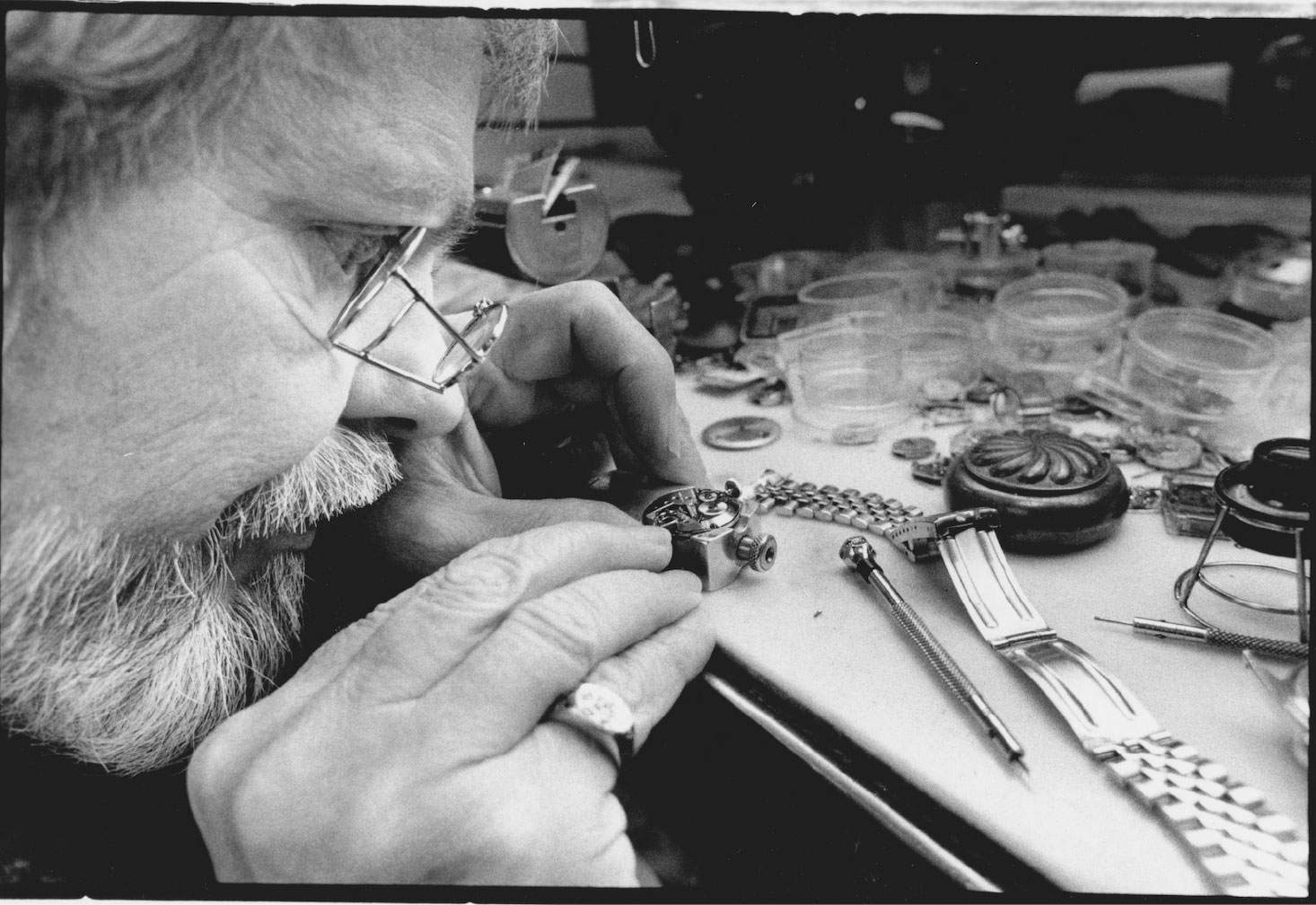

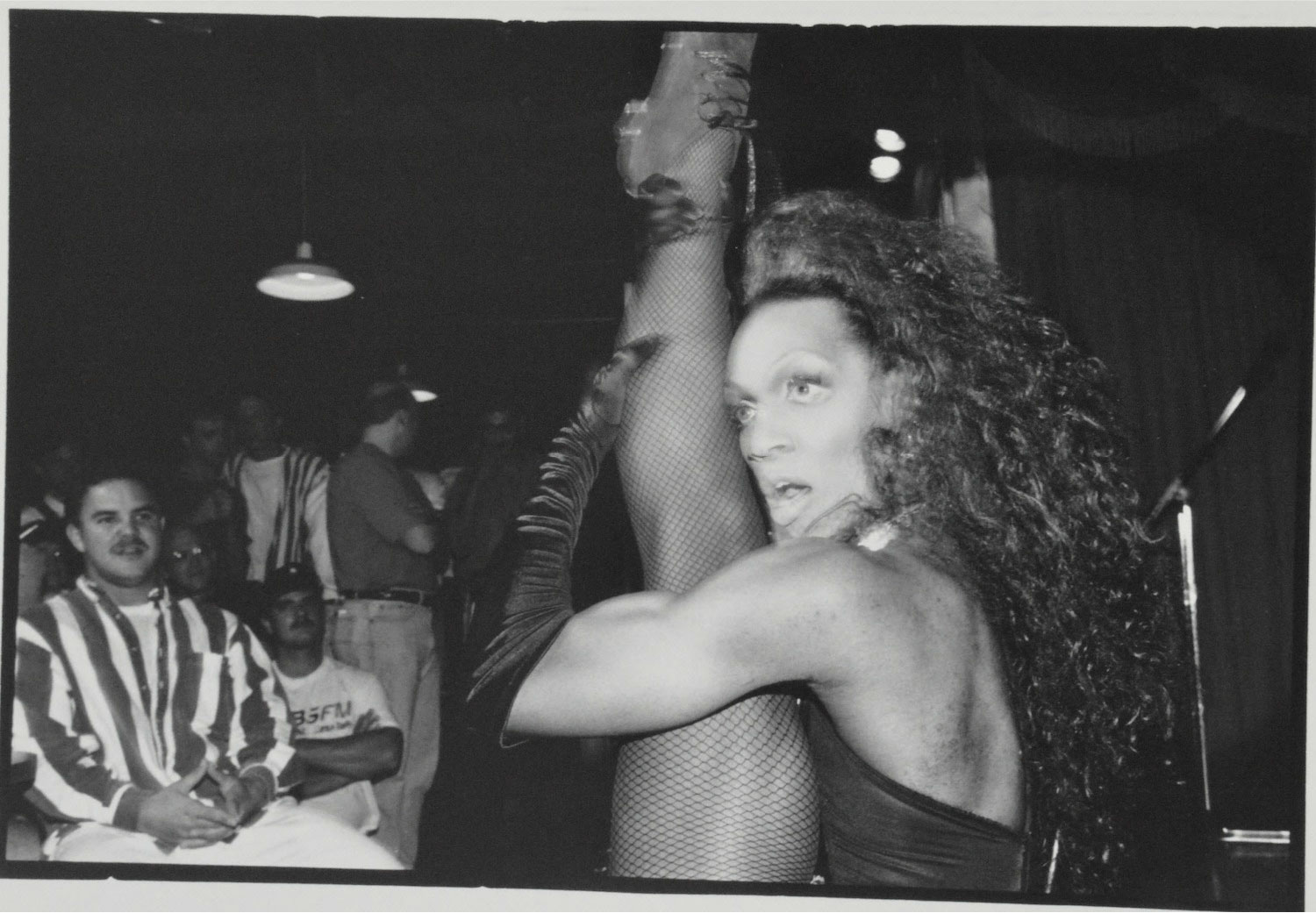

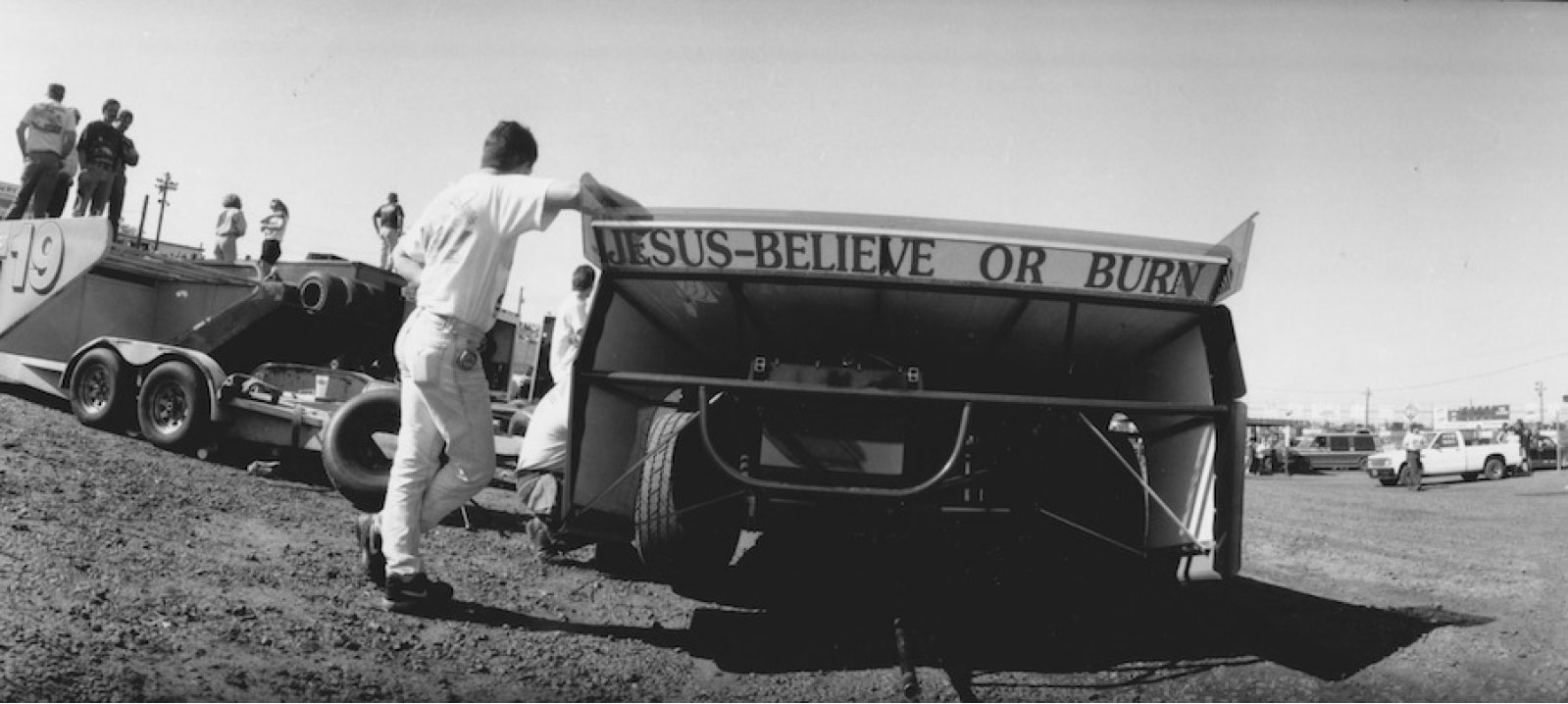

1993: Matt Strelecki, art director for Atlanta Magazine, prints a photo essay of my photographs of immigrants in a special issue on race under the title The New Minorities. This launches a two-year collaboration, and I find myself immersed in the beginning explosions of Atlanta dance clubs– Body Language; the survivors of the Old South either thriving (dirt track car racing) or on their last legs (Fulton County Stadium)–Vanishing Atlanta; and my favorite, 3 AM–Life in the city from Charlie Brown’s Cabaret to the Waffle House and Leather ‘n Lace “modeling studio.” The latter is never published, a victim of staff turnover at the magazine. These series take me into the heart of life in 1990s Atlanta, a life that all-too-quickly fades away.

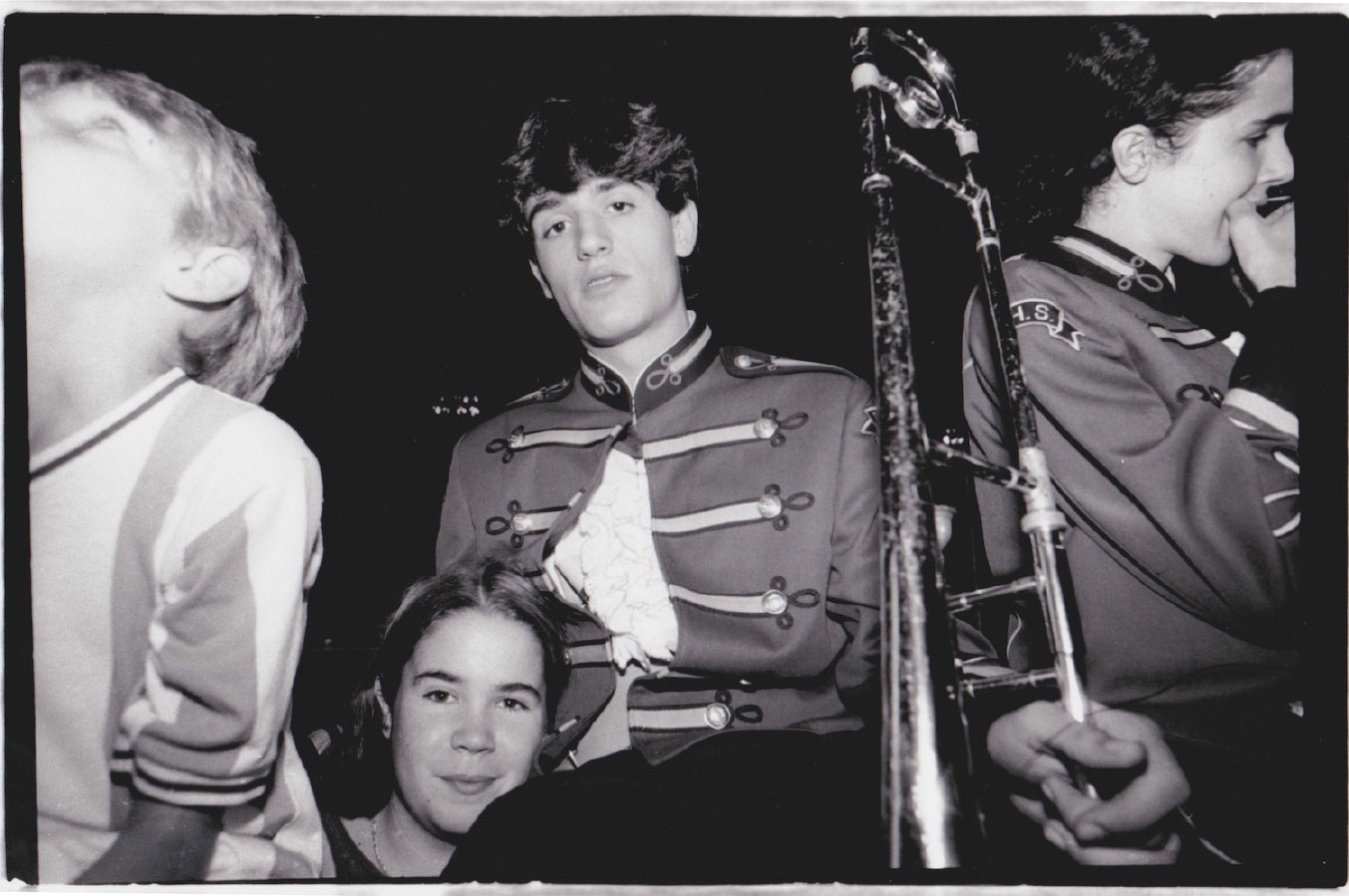

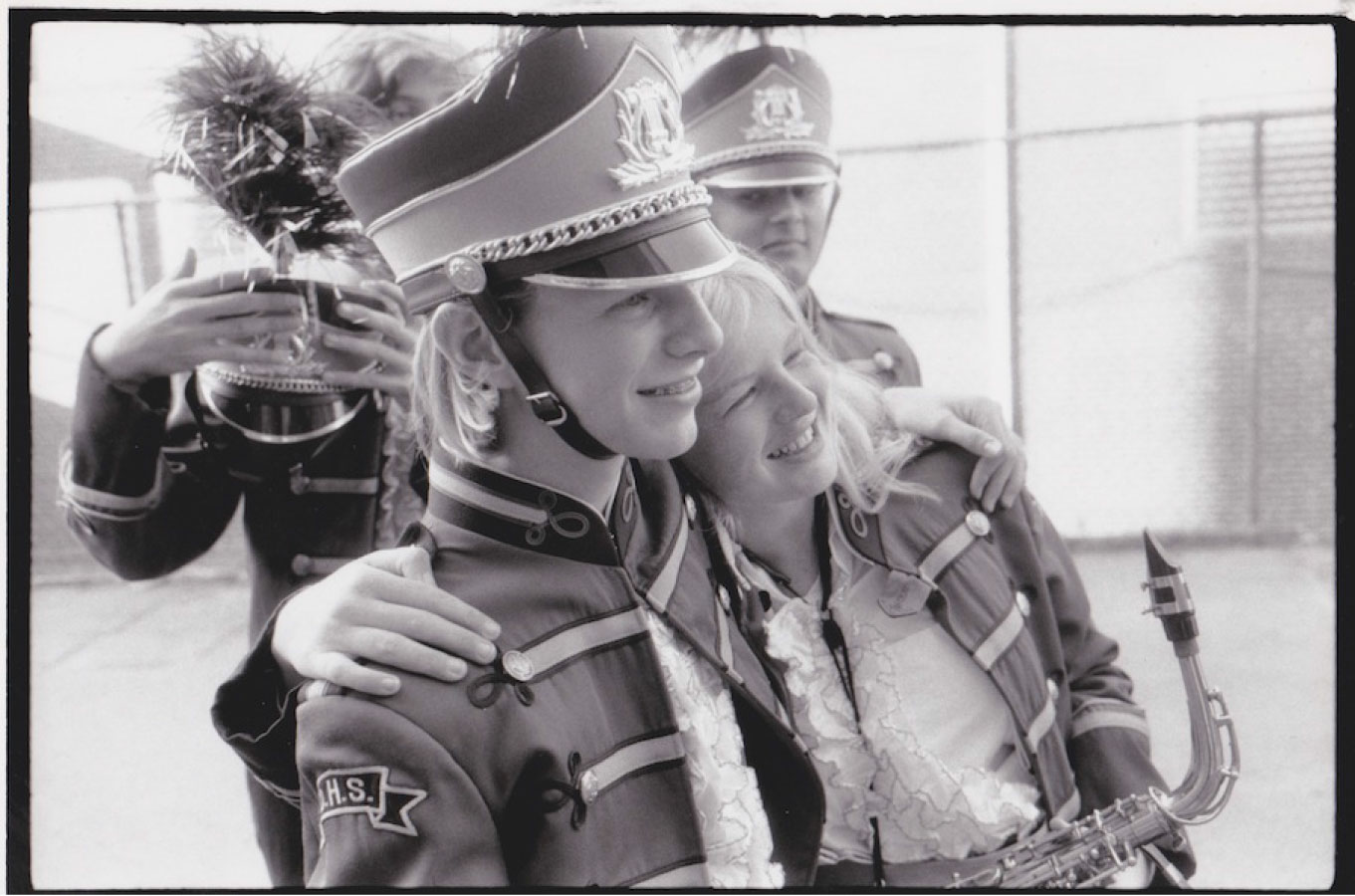

1996: Danny is sixteen, a junior at Decatur High School. He’s in the marching band, Maryann teaches history at the same school. Watching Danny in the band, I see a world I hadn’t seen before. A world without Michael, but a world with Danny. His world, his life. It’s all changing. I spend a full year filming him and the other kids in the band, immersing myself in their lives though I will always be an outsider. With my friend James Jernigan I make a film, The Band, a love letter to Danny and his world. It’s broadcast on the PBS series POV.

1996-1998: Leah is born, Danny goes to college, and Celia is conceived. Maryann’s and my parents are all in Los Angeles, where we started. We return, leaving Atlanta behind.

My Atlanta was a heady mix of old and new, decay and birth, loss and renewal. My life and the life of my home were intertwined as never before. I drank it all in, reveled in the pain and chaos of new birth. And I photographed it.

Photos

P.1–Abandoned warehouse

P.2–Top: Abandoned bus depot; Bottom: Fotografitti

P.3–Top: Kenny Leon and Carol Mitchell-Leon in Fool for Love at the Actors’ Express

Bottom: Jon Ludwig and friend in The Heaven/Hell Tour at the Center for Puppetry Arts P.4–Top: Angels in America at the Alliance Theater

Bottom: Felicia Rashad in Blues for an Alabama Sky at the Alliance Theater P.5–Inside the installation In the Land of the Blind the One-Eyed Man is King P.6–Top: Woodgate Apartments, Chamblee; Bottom: Vietnamese sisters, Riverdale P.7–Woodgate Apartments, Chamblee

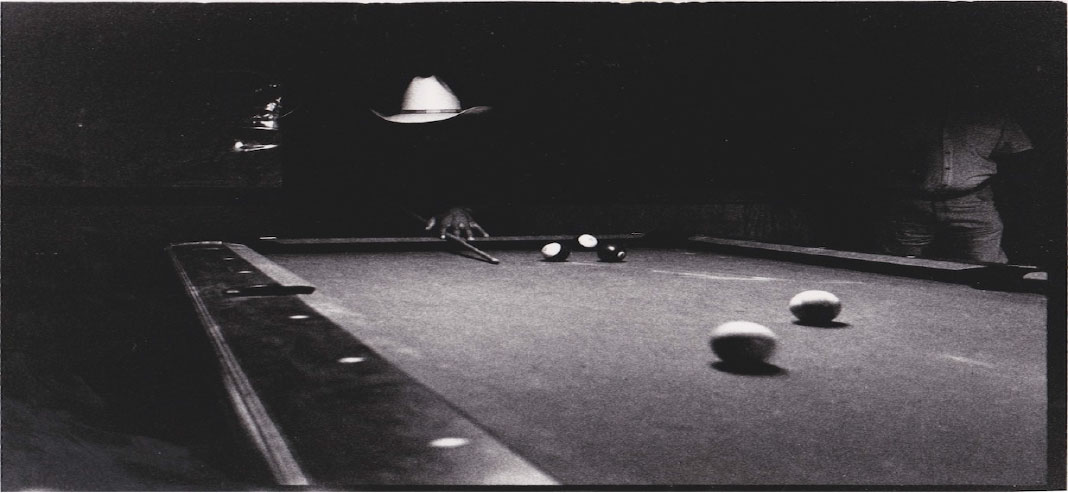

P.8–Top: Mustacho Miguel’s, Chamblee

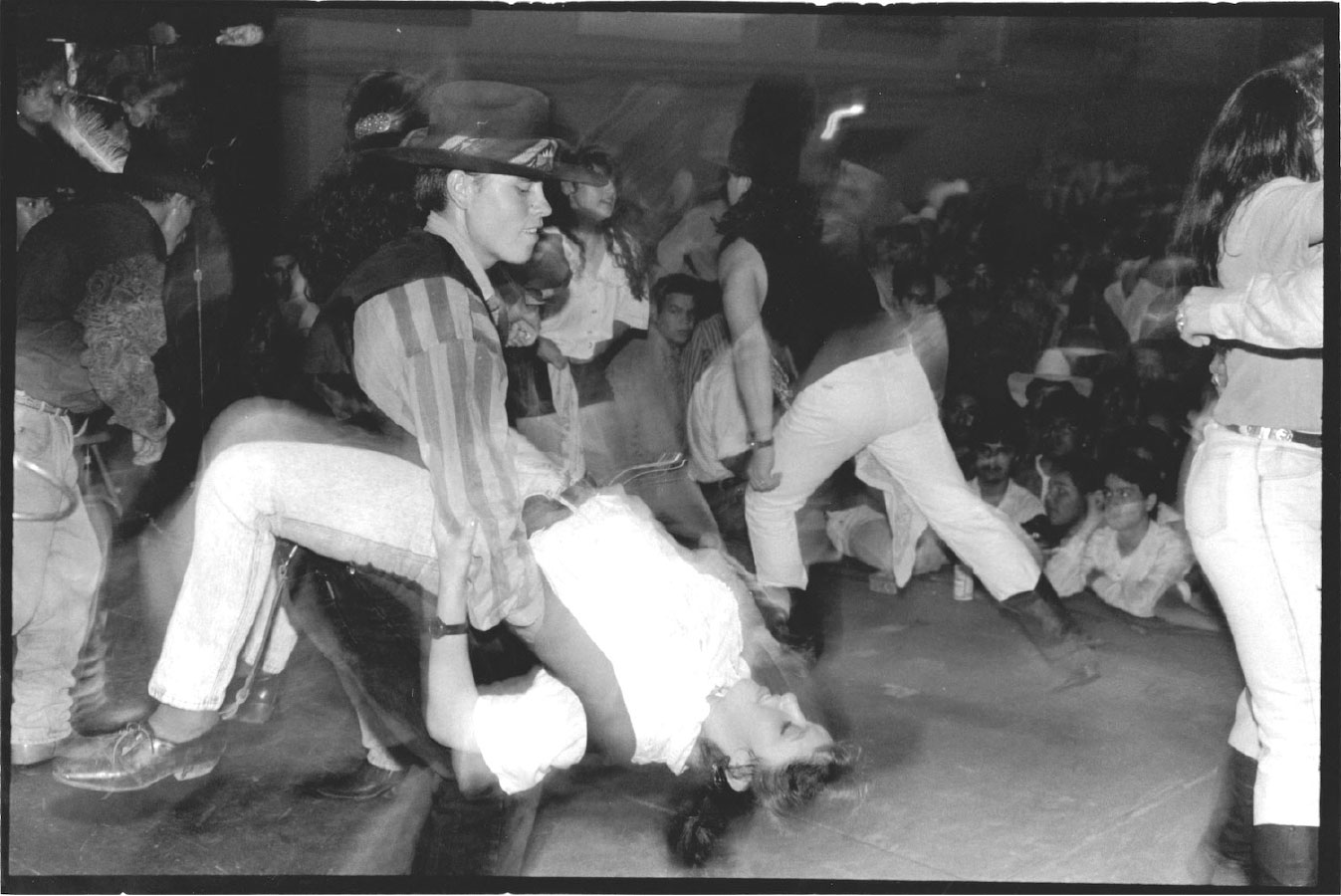

Bottom: Dancing La Quebradita at the International Ballroom, Doraville

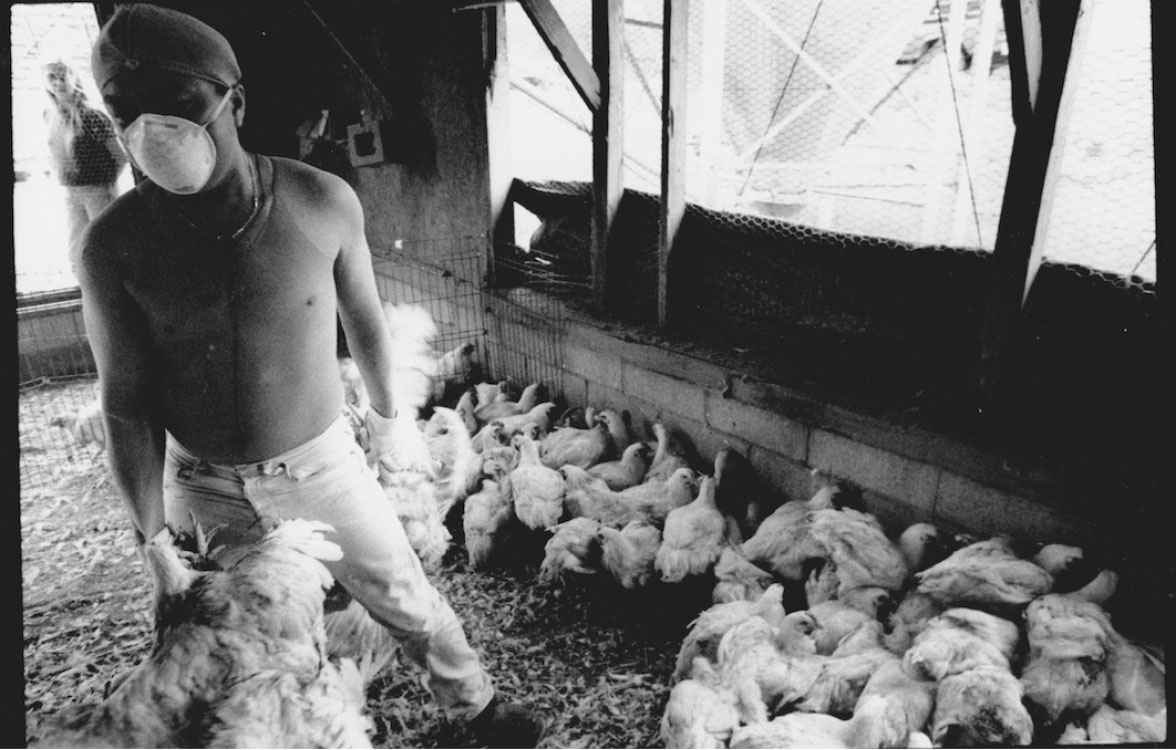

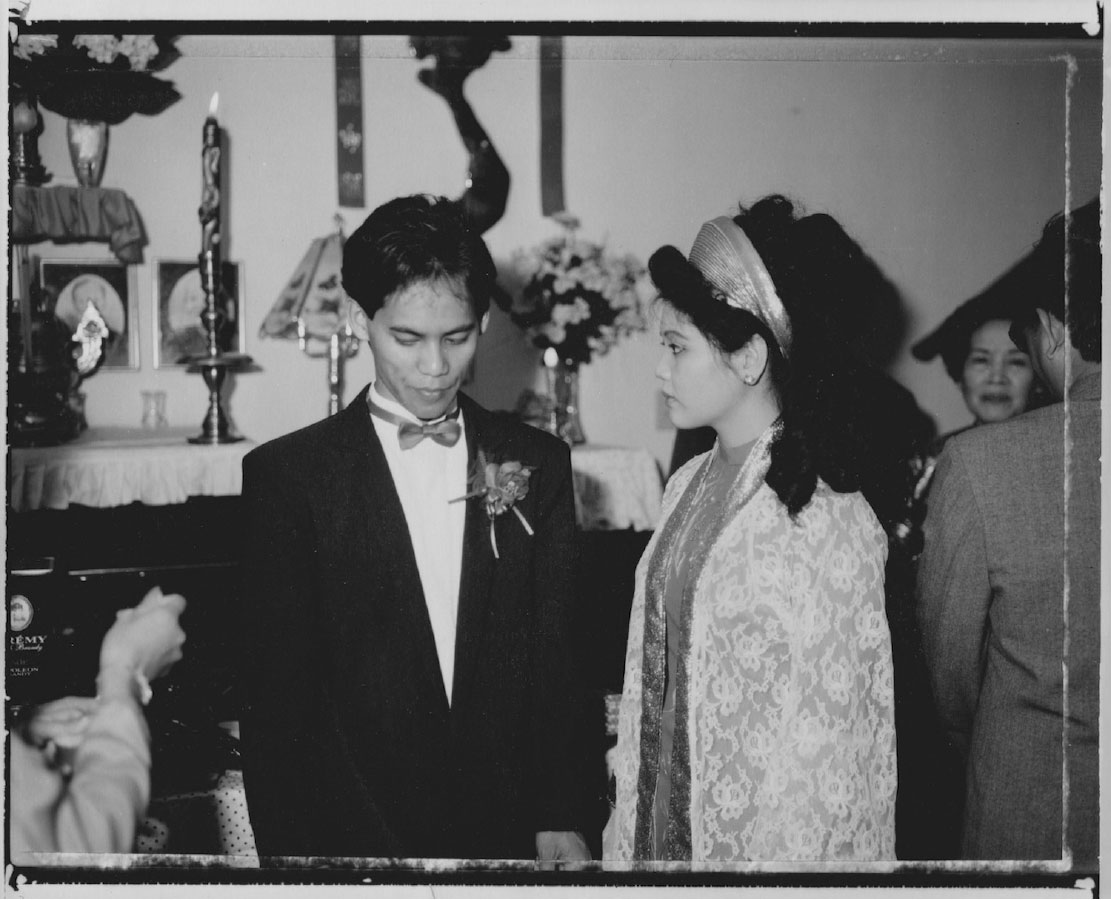

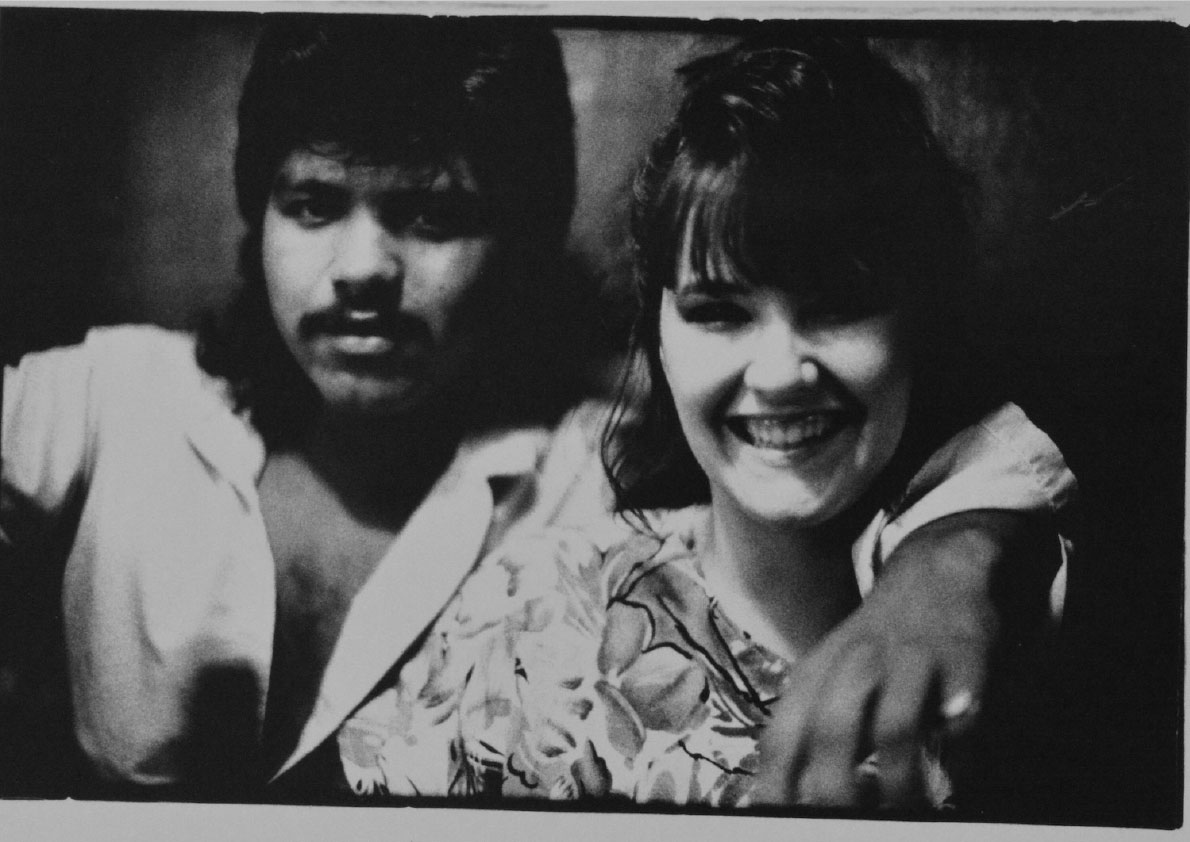

P.9–Top: Chicken farm, North Georgia; Middle: Vietnamese wedding, Doraville Bottom: Mustacho Miguel’s, Chamblee

P.10–Polaroid portraits shot at the Doraville Boxing Gym

P.11–From My Son, Michael D, Died when He was Nine Years Old, Nexus Art Center

P.12–Top: Atlanta Magazine Body Language page; Bottom: Leather ‘n Lace from 3 Am.

P.13–Top: Watchmaker from Vanishing Atlanta; Middle: Charlie Brown’s Cabaret from 3 AM

Bottom: Dirt racetrack from Vanishing Atlanta Pl14–Top: Members of the band; Middle: Danny and a friend